One comment I hear frequently from my students in regard to a writer’s work is that it “flows well,” or not so much. What does it mean to say that fiction flows?

Writing Tip for Today: To a lot of readers, flow probably means that as one is reading along, nothing jumps out to slow or stop the reader. For pros, flow points more to one of three areas: transitions, logic and conflict.

- Transitions: As I’m always reminding, a writer’s first job is almost always to orient the reader in time and space. As time moves (flows!) along in the story, the writer must erect signposts so the reader doesn’t get lost or confused. By using simple transitions (one day) and presenting them right away in a scene, the reader is able to move onto the scene’s business, sure of where and when the scene takes place. This is especially true if the story jumps back and forth in time (flashback or back story). The moment you confuse your reader, you’re in danger of losing that reader.

- Logic: As you revise a story, you are likely to need to move parts of the story forward, backward or change important details to improve character motivation and make the stakes higher. Sometimes by cutting and pasting, the logical progression of events gets scrambled and/or the reason why a character would do or say something is lost upon the reader. Let’s say, for instance, that you write a scene where one character has come in from a rainstorm and is toweling off her hair. Later, you move the scene to a week after it originally occurred. You must answer the question: Is it still raining a week later? My advice? Read your story out loud, preferably to another writer. You’ll be using more of that logic-oriented side of the brain and errors will be easier to spot. And although it’s tough, sometimes you must “kill some darlings” because they no longer make sense.

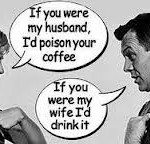

- Conflict: Anytime a scene does not build tension, flow is interrupted. A reader might not be able to say exactly why, but if you protect your character by shielding him/her from catastrophe, the reader will lose interest. When you write conflict, things don’t need to explode or catch fire. But the two principal characters in the scene must be at cross-purposes in some way and there must be an outcome of the character wins, loses or it’s a draw (not recommended). For every scene you write, ask yourself what each character wants from the other as a starting point.

Great article, Linda. I will tweet your valuable advice to NY followers.

All the best.

Adam

iwritereadrate.com