The way any given scene ends and how the following scene begins is one of fiction’s most important elements to keep readers reading. Yet there is more to good technique than simply leaving white space between scenes.

The way any given scene ends and how the following scene begins is one of fiction’s most important elements to keep readers reading. Yet there is more to good technique than simply leaving white space between scenes.

Writing Tip for Today: What are some ways to connect separate scenes in a way that engages readers? The three primary ways writers get readers from scene to scene are by using a blank space, also called a hiatus; by inserting a tease or cliffhanger at the end of a scene; and by writing so that “boring” or mundane details not relevant to the story are omitted.

Omit Boring Stuff

Writers are often told to “skip the boring stuff,” so it makes sense to use a simple transition sentence. The more a writer embellishes or otherwise fancies up a simple transition, the more likely readers will become confused or frustrated. “Time passed” is the most direct way to ensure that readers understand “when and where” they are in the scene to follow. I tell writers not to bend over backwards trying to come up with an original transition. Instead, be as succinct and direct as possible. The transition sentence or phrase only has one job: to let readers know there’s been a change in time and/or location. If you are changing character viewpoint at a scene break, use the new character’s name at the beginning of the sentence. Some writers also do not indent the first sentence of the new POV.

Using Cliffhangers

The cliffhanger is a device that piques readers’ curiosities enough to be compelled to turn the page. It’s like a spark plug—the real power rests in that gap where the sparks jump across. Yet a poorly constructed cliffhanger may do more damage than good. If you end a scene with an unresolved question, it’s important to allow readers’ imaginations to consider answers without forcing them to guess about the scene’s outcome. One mistake I see regularly is scenes which end too soon. This leaves readers with too many possibilities to consider and if the following scene jumps ahead too far, the gap between scenes ceases to be a cliffhanger and becomes ineffective. You risk losing readers to confusion or frustration if you fail to bring your cliffhanger to a place with a clear sense of direction. Remember, readers are looking for emotional cues—they want to figure out not only what happens but why it happens. Readers do this by understanding character motivations, but if they aren’t given enough emotional information, readers can lose interest. Like a spark plug, a good cliffhanger gives power to the story, raises tension and helps invest readers. But they must also be able to jump across that emotional gap.

Conflict Avoidance

I think one reason for poor scene transitions lies at least partly in our desire to avoid conflict. We writers can stage a scene ripe for conflict well enough and we’re frequently able to get our characters standing nose to nose. Yet I see many manuscripts where the actual conflict is either aborted or drawn out too long. The Rule of Three is helpful in balancing a high-tension scene, ensuring that you write enough of the actual conflict but not so much that it feels repetitive. In transitioning from one scene to another, check to be sure the height of the conflict hasn’t been banished into the hiatus between the scenes. Summarizing that they fought and then made up is so much easier than showing readers what their conflict looks like. When you end one scene and then begin the next, be sure you haven’t left the most important emotional cues unwritten. Getting from one scene to the next should be smooth, so readers don’t even notice when they’ve transitioned.

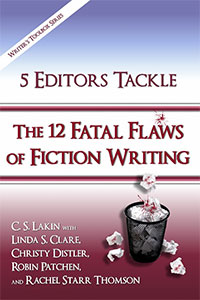

There’s still time to get a great deal on Five Editors Tackle the Twelve Fatal Flaws of Fiction Writing. All during December, if you buy the paperback as a gift for a writer friend, you’ll get a free e-copy to keep for yourself!